Country HTA Snapshots: Australia, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan

HTA serves as a crucial process to decide whether a medicine or health technology should be accessible within a health system. It assesses the potential impact of the intervention, considering both its costs and benefits. Additionally, HTA aids in providing guidance on the safe and effective prescription of medicines and technologies, outlining their integration into existing treatment pathways and service delivery systems. Given the constraints of finite health and medicines budgets, HTA plays a pivotal role in evaluating if a medicine or technology genuinely adds value to a health system, helping allocate resources judiciously.

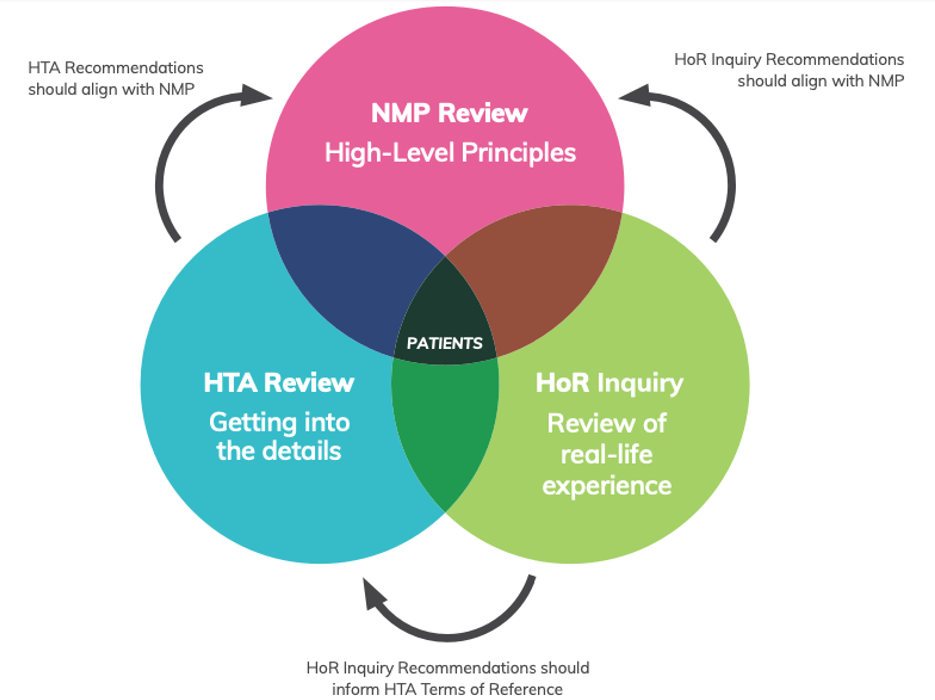

Australian process for gaining access is notably prolonged. Unlike some countries, Australia lacks an early access program. The Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) conducts HTA for new products, without specific evidence rules for orphan drugs. PBAC data guide the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) in deciding formulary inclusion. Although there’s no formal willingness-to-pay amount, orphan drugs often face rejection before acceptance at an agreeable price. In cases of PBS denial, the Life Saving Drugs Programme (LDSP) provides funding, regardless of cost-effectiveness, for medications offering increased life expectancy in serious conditions without alternative treatments. Despite eventual coverage for most drugs, the time from regulatory approval to patient access can extend beyond six years.

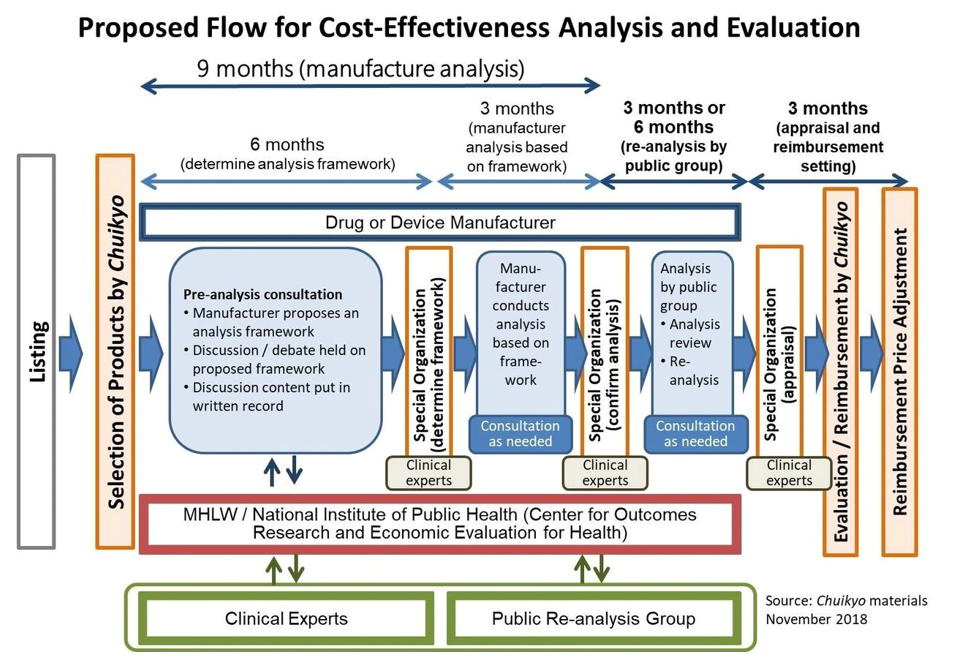

In Japan, according to these rules, the system must reimburse all drugs at the requested price within 60-90 days of approval. Notably, drugs exclusively for rare diseases skip additional HTA processes. For drugs addressing both orphan and non-orphan conditions, a year of real-world data collection is mandated. Afterward, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare establishes a price using a complex formula, factoring in improvements over existing therapies, innovation rewards, and reductions for costs exceeding a specified level per QALY.

Interestingly, cost per QALY thresholds are 1.5 times higher for mixed-use drugs compared to non-orphan drugs.

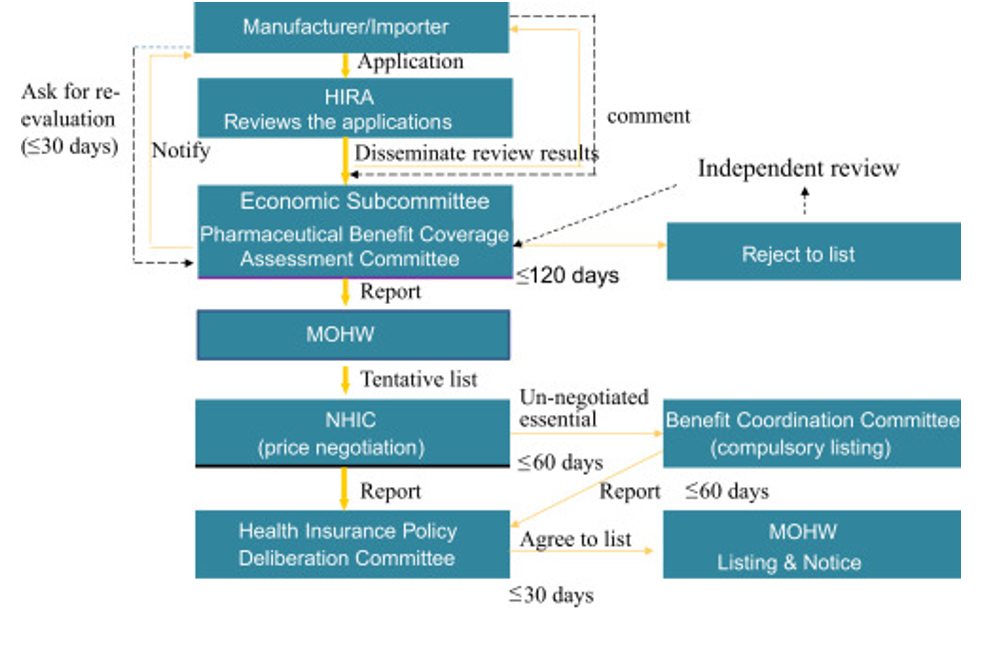

In South Korea, according to rules established in 2015, if orphan drugs can demonstrate significant clinical effectiveness, the national insurance system will pay a price based on those in other major markets. However, due to limited proof for most products, they don’t fall into this category. If a drug is reimbursed in three of the seven major pharmaceutical markets, the health system is willing to negotiate a price. Despite attempts, this approach has seen limited success, covering only 56% of approved orphan drugs. The challenges include manufacturer reluctance to seek reimbursement, official concerns about increased spending on rare diseases, a typical one-to-three-year assessment period for applications, and a 30% rejection rate.

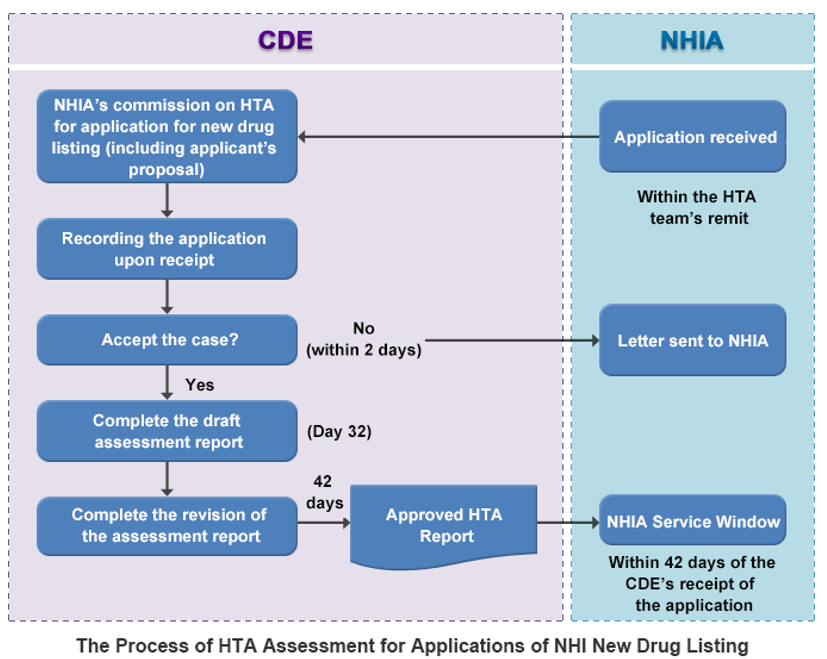

In Taiwan, country’s HTA system assesses both orphan and non-orphan drugs, incorporating a cost-per-QALY evaluation for both. While the willingness-to-pay figure is higher for orphan drugs, it is not disclosed publicly. Additionally, although there is a dedicated budget for rare disease treatments, it applies only to medications for 236 officially recognized rare diseases. Even when a drug is reimbursed, stringent conditions may limit access. For instance, Nusinersen sodium, a treatment for spinal muscular atrophy, is covered for only 10% of eligible patients. Concerns about high costs are likely to impede any swift changes.